Deriving the intrinsic properties of high-redshift dusty star-forming galaxies, magnified by strong gravitational lensing

The principal focus of my Ph.D. dissertation was a multi-wavelength study of superbly luminous dusty star-forming galaxies (DSFGs) at redshifts 1 < z < 3.5, identified as part of the PASSAGES project (Planck All-Sky Survey to Analyze Gravitationally-lensed Extreme Starbursts). By examining DSFGs that are gravitationally lensed by an intervening cluster or galaxy, one can recover details of the structure of gas and dust distributions and star formation activity at sub-kiloparsec physical scales. This spatial resolution is practically unreachable for existing telescopes without the aid of a "cosmic telescope" in the form of strong lensing.

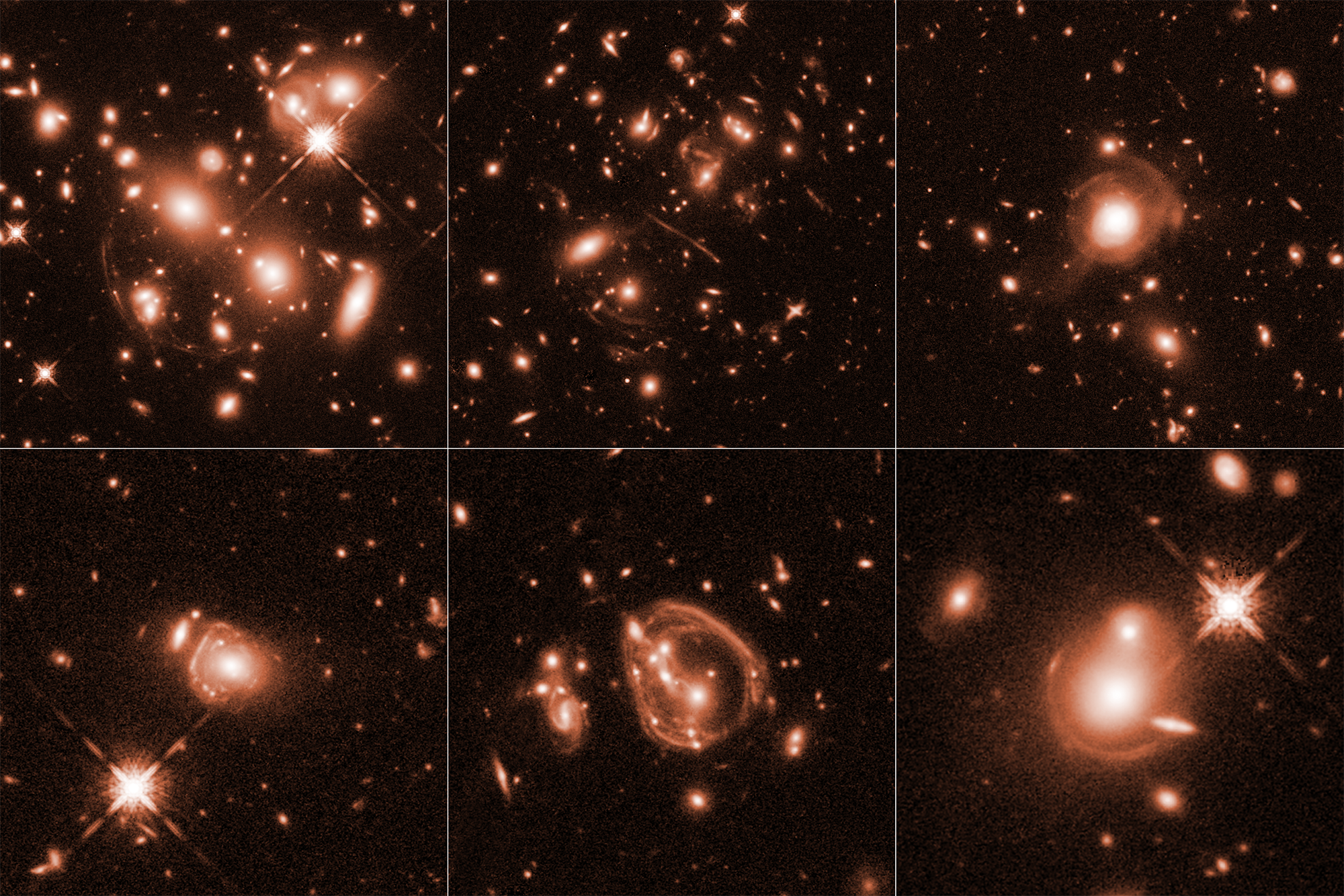

Multi-wavelength observations from Hubble WFC3 at 1.6 μm, the Jansky Very Large Array at 6 GHz, and Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array at 1mm and 3mm provided constraints in deriving lens models for the sample. Our sources were selected from the Planck all-sky survey, as detailed by Harrington et al. 2016 and Berman et al. 2022. These hyper-luminous dusty starbursts have been found with overwhelming frequency to be spectacular gravitational lenses, often with near-complete Einstein rings (see our press release from June 2017). Their intrinsic brightness from rapid star formation (on the order of 1000 solar masses per year) combined with the amplifying effect of gravitational lensing places them amongst the ranks of the most luminous galaxies known at this time.

In Kamieneski et al. 2024a, we examined the intrinsic sizes of the dust continuum emission for these extreme galaxies, which effectively reveals the spatial distribution of star formation. We found that they were consistent with large, extended disks, rather than the compact nuclei of star formation found often in local ultra-luminous infrared galaxies. This was a surprising result, as it had been previously suspected that these extreme dusty starbursts would be assembling stellar mass at or near the Eddington limit, which would subsequently shut down and quench star formation after a short period. Instead, their submillimeter morphologies suggest that stellar feedback alone might not be sufficient to extinguish their star formation.

Faraday rotation measure synthesis of nearby edge-on galaxies

Through the CHANG-ES (Continuum Halos in Nearby Galaxies-- an EVLA Survey) project, I studied Faraday rotation in a sample of nearby disk galaxies. Linearly polarized light (produced most commonly as synchrotron radiation) has a characteristic position angle. When the light travels through a magnetized plasma, this intrinsic polarization orientation is altered, in what is known as the Faraday effect.

Linear polarization can be represented equivalently as a superposition of right-hand and left-hand circular polarization, which have slightly disparate indices of refraction in a magnetized medium. In turn, the plane of polarization is rotated by an amount proportional to the wavelength squared (λ2). The corresponding constant of proportionality is known as the rotation measure, or RM. The RM itself is dependent on the electron density and the component of the magnetic field parallel to the line-of-sight.

In measuring this spectral variation of the polarization angle, we have a unique opportunity to probe magnetic fields in nearby galaxies. For a meaningful detection, one requires a sufficiently large bandwidth, such as can be offered by the Jansky Very Large Array in the radio regime. Future facilities like the Square Kilometer Array will fundamentally revolutionize the study of Faraday rotation and, in broader terms, our understanding of cosmic magnetism itself.